Don Blankenship lost at the Supreme Court on Oct. 10. He had sued NBC, CNBC, Fox News, MSNBC, and other media properties for defamation, and he appealed to the high court to redress his loss at the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals. His case was rejected because he is a public figure, and the law protects lies told about public figures. Justice Clarence Thomas used the case to argue that the Court needs to rewrite the law, giving public figures back some legal protection of their good names.

Never a Felon

On April 5, 2010, an explosion killed 29 miners at West Virginia’s Upper Big Branch mine, the worst mining disaster in 40 years. Blankenship was in the middle of it as CEO. In the fallout after the explosion and years later, he was convicted of conspiring to violate federal mine safety standards. He went to trial and beat two felony charges but lost on the misdemeanor. Blankenship had to serve a year in prison upon conviction. If a news outlet later called him a felon, should he be able to sue? That’s what the case is about.

People deemed public figures generally or for a specific story usually can’t sue others for defamation. The Supreme Court created this rule in 1964’s New York Times Co. v. Sullivan case. About it, Justice Thomas wrote:

“It decreed that the Constitution required ‘a federal rule that prohibits a public official from recovering damages for a defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct unless he proves that the statement was made with “actual malice” — that is, with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.’ The Court did not base this ‘actual malice’ rule in the original meaning of the First Amendment.”

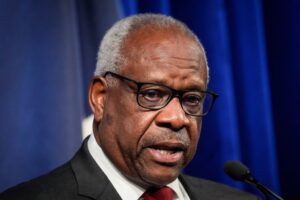

Justice Clarence Thomas (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

In 2018, Republican hopefuls in West Virginia vied for the nomination to challenge Democrat Joe Manchin for US Senate. Blankenship threw his hat in the ring until, his complaint says, the media outlets he sued “derailed [his] candidacy by falsely publishing that [he] is a ‘convicted felon.’” He went on to say, “The damage was irreparable. No person convicted of a felony has ever been elected to the United States Senate.”

Thomas Hints at New Rules

Under the Sullivan standard, Blankenship will never recover because he can’t prove news outlets knew for sure he wasn’t a felon but said so anyway. Blankenship asked the Court to rewrite its created law, and Justice Thomas is ready, willing, and able to do it – in a suitable case. Thomas agreed to reject Blankenship’s case because of a detail in West Virginia’s state law. In another case, however, he would rewrite Sullivan, ditching the actual-malice rule. The Justice quoted himself from another opinion, writing:

“And the actual-malice standard comes at a heavy cost, allowing media organizations and interest groups ‘to cast false aspersions on public figures with near impunity.’ The Court cannot justify continuing to impose a rule of its own creation when it has not ‘even inquired whether the First or Fourteenth Amendment, as originally understood, encompasses an actual-malice standard.’”

The impact on public discourse of such a move is hard to underestimate. Media outlets would likely proceed with great caution, not publishing some controversial stories, as would individuals on social media – especially those with something to protect from suit. This might yield far fewer defamatory instances for public figures and definitely decrease reporting and posting on contentious stories. That may be the price if the Court rewrites the rule it implemented. Justice Thomas’ writing does not have the force of law but may prove highly influential in how other Justices and lower court judges see the issue and rule on future cases.