All things are no longer considered.

There is perhaps nothing the news media adores more than talking about itself. So, when quarter-of-a-century NPR editor Uri Berliner spilled the beans about a lack of “viewpoint diversity” at National Public Radio, it predictably opened Pandora’s box. That the outlet has turned hard left is scarcely worth headlining, but there is value in talking about how it got to where it is now.

So, just where is it? NPR’s audience has taken a nosedive. Its flagship morning program All Things Considered no longer considers all things. Is this a surprise coming from “an insulated cadre of people … [who] have a hard time with people who are different,” as commentator Juan Williams put it? Or is this par for the course from a staff who are 87-0 Democratic voters, as catalogued by Berliner?

Although there has been some pushback by the tax-funded organization’s Editor-in-Chief Edith Chapin, the whistleblower used data to back up his assertions: In 2011, 26% of NPR listeners self-identified as conservatives, 23% claimed a centrist political perspective, and 37% said they were liberal. But by 2023, only 11% claim to be conservative, 21% say they land in the middle, and 67% call themselves somewhat or very liberal. Why the change in listener demographics? Berliner answered that cogently by illustrating NPR’s lopsided coverage of three major news stories:

- Russia collusion

- The Covid Wuhan lab leak

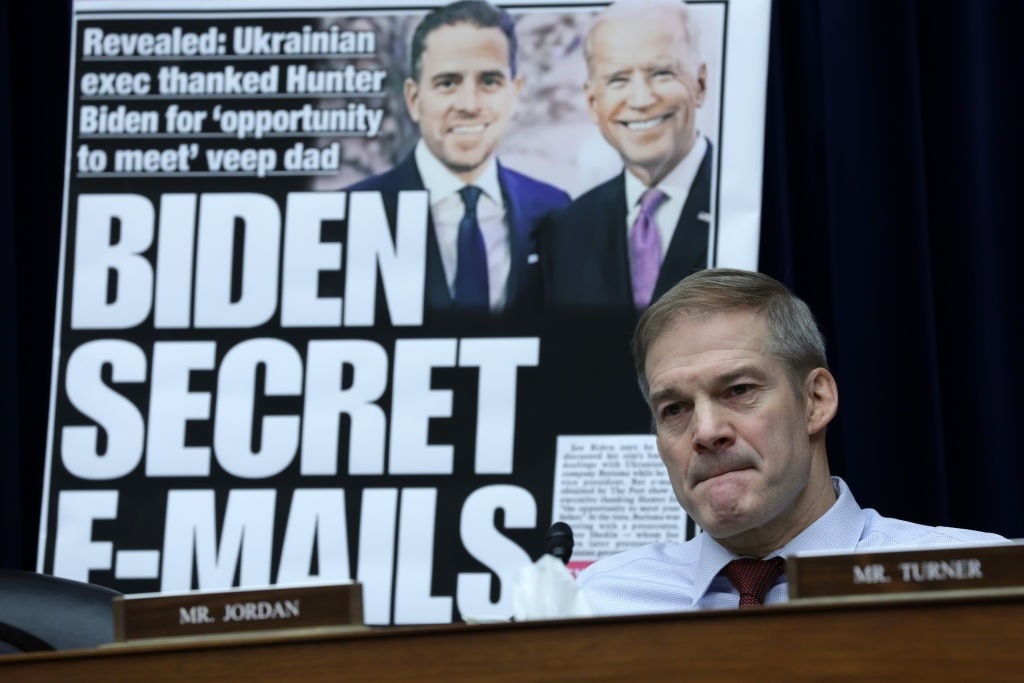

- The Hunter Biden laptop story

Indeed, there is more evidence of left-leaning bias, but this was really all Berliner needed to demonstrate the political bent of public radio. In each case, he documented either bonding with anti-Republican sources – like Rep. Adam Schiff (D-CA) in the Russia collusion boondoggle — or the error of omission by ignoring the Hunter Biden laptop story. To sum up, Berliner’s hypothesis that his employer is no longer a remotely balanced news source becomes crystal clear.

Of course, not all news sources are balanced, and there is plenty of room for niche reporting. But NPR’s problem is twofold: one, it is part of a public broadcasting entity partially funded by tax dollars, and, two, it advertises as “Free and independent journalism.” How independent is a media outlet when all its employees are of one political persuasion?

(Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Berliner is obviously unhappy with such a biased version of the organization he joined 25 years ago. He asserted (with evidence) that “we don’t have an audience that reflects America,” “politics were blotting out the curiosity and independence that ought to have been driving our work,” and “the most damaging development at NPR: the absence of viewpoint diversity.”

His final point: “We happen to have a very powerful tool for answering such questions: journalism. Journalism that lets evidence lead the way.” Unfortunately, Berliner hasn’t entirely caught up with the new journalistic paradigm, which has turned traditional J-school on its head.

This was outlined recently at Liberty Nation by National Correspondent Joe Schaeffer, who examined the curricula at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University (ASU). Its vision:

“We are guided by the following VISION: We believe in the power of media to inform and inspire society to solve challenges big and small.

“That vision is inspired by this MISSION: We educate and empower communicators to create an informed and inclusive society, advancing understanding and connection among creators, audiences, industry and the academy.”

Schaeffer correctly noted, “The overarching idea, which has nothing to do with any real claim to practicing journalism on a serious level, is to push or manipulate readers or viewers into accepting the particular partisan views of the writers or video reporters.”

For more than two centuries, the American public has relied on the First Amendment to the Constitution to protect freedom of the press. However, this amendment does not address the issue at hand. It delineates Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of or abridging the freedom of the press. And Congress is not the problem here.

The dilemma lies with the media organization itself. Evident in this argument is that places like NPR no longer want to appeal to broad swaths of the electorate. That is certainly their right, just as a citizen has the right not to listen or read what is being said or published there. The real issue is that NPR is a public institution primarily funded by the American people. Berliner’s complaints are valid because NPR does not provide news that appeals to conservatives or even moderates — and that is its Waterloo.